Gentle Introduction To Typescript Compiler API

Read more

TypeScript extends JavaScript by adding types, thereby enhancing code quality and understandability through static type checking which enables developers to catch errors at compile-time rather than runtime.

The TypeScript team has built a compiler tsc to process TypeScript type annotations and emit JavaScript code, however, the compiler is not limited to just compiling TypeScript code to JavaScript, it can also be used to build tools and utilities around TypeScript.

In this article, you'll explore the TypeScript Compiler API, which is an integral part of the TypeScript compiler that exposes various functionalities, enabling you to interact with the compiler programmatically.

The article is organized into different use cases each of which will introduce you to a new aspect of the Compiler API, and by the end of the article, you'll have a thorough understanding of how the Compiler API works and how to use it to build your own tools. Keep in mind the use cases are not complete, they're just to demonstrate the concept.

What is A Compiler?

A compiler is a specialized software program that translates source code written in one programming language into another language, usually machine code or an intermediate form. Compilers perform several tasks including lexical analysis, syntax analysis, semantic analysis, code generation, and more.

Compilers come in various forms, serving different needs, to my understanding TypeScript is a Source-to-source compiler, which means it takes TypeScript code and compiles it into JavaScript code.

What is The TypeScript Compiler?

The TypeScript Compiler (tsc) takes TypeScript code (JavaScript and type information) and compiles it into plain JavaScript as the result while in the process it performs type checking to catch errors at compile time rather than at runtime.

For the compilation to happen you need to feed the compiler a TypeScript file/code and the configuration file (tsconfig.json) to guide the compiler on how to behave.

// file.ts

function IAmAwesome() {}// tsconfig.json

{

"compilerOptions": {

"target": "es5",

"module": "commonjs",

"outDir": "./dist",

"strict": true

}

}Run the following command to compile the code:

tsc file.ts --project tsconfig.jsonDepending on the configuration, the compiler will generate the following files:

dist

├── file.js

├── file.js.map

├── file.d.ts- JavaScript code: The compiler will output JavaScript code that can be executed later on.

- Source map: A source map is a file that maps the code within a compressed file back to its original position in a source file to aid debugging. It is mostly used by the browser to map the code it executes back to its original location in the source file.

- Declaration file: A file that provides type information about existing JavaScript code to enable other programs to use the values (functions, variables, ...) defined in the file without having to guess what they are.

The TypeScript compiler generates declaration files for all the code it compiles if enabled in tsconfig.json.

What is The TypeScript Compiler API?

The TypeScript Compiler API is an integral part of the TypeScript compiler that exposes various functionalities, enabling you to interact with the compiler programmatically to do stuff like

- Manual type checking.

- Code generation.

- Transform TypeScript code at a granular level.

and more.

TypeScript Compiler API is a lot of interfaces, functions, and classes.

Why would you use the Typescript Compiler API?

Using the TypeScript Compiler API has several benefits, particularly for those interested in building tools around TypeScript. You could utilize the API

- Write a Language Service Plugin

- To do Static Code Analysis

- Or even to build a DSL (Domain Specific Language).

- Custom Pre/Post build scripts.

- Code Modification/Migration.

- Use it as a Front-End for other low-level languages.

Angular recently introduced the Standalone Components, which is a new way to write Angular components without the need to create a module. Angular team created a migration script that does this automatically, and it's using the Typescript Compiler API.

There are a few interesting projects that utilize the Typescript Compiler API, such as:

- Compile JSONSchema to TypeScript type declarations

- TypeScript AST Viewer

- TypeScript API generator via Swagger scheme

Use Case: Enforce One Class Per File

You're going to use the Typescript Compiler API to enforce one class per file. This is a common rule that is used in many codebases.

It might be a bit confusing at first, but don't worry, It'll get simpler as you go.

Hint: I strongly recommend you check the code again before going to the next use case.

const tsconfigPath = './tsconfig.json'; // path to your tsconfig.json

const tsConfigParseResult = parseTsConfig(tsconfigPath);

const program = ts.createProgram({

options: tsConfigParseResult.options,

rootNames: tsConfigParseResult.fileNames,

projectReferences: tsConfigParseResult.projectReferences,

configFileParsingDiagnostics: tsConfigParseResult.errors,

});

/**

* Apply class per file rule

*/

function classPerFile(file: ts.SourceFile) {

const classList: ts.ClassDeclaration[] = [];

// file.forEachChild is a function that takes a callback and

// calls it for each direct child of the node

// Loops over all nodes in the file and push classes to classList

file.forEachChild(node => {

if (ts.isClassDeclaration(node)) {

classList.push(node);

}

});

// If there is more than one class in the file, throw an error

if (classList.length > 1) {

throw new Error(`

Only one class per file is allowed.

Found ${classList.length} classes in ${file.fileName}

File: ${file.fileName}

`);

}

}

const files = program.getSourceFiles();

// Loops over all files in the program and apply classPerFile rule

files

.filter(file => !file.isDeclarationFile)

.forEach(file => classPerFile(file));In this code you're doing the following:

- Create a program from tsconfig so you've access to all files in the project.

- Loop over all files in the program and apply the rule.

- The rule is simple, if there is more than one class in the file, throw an error.

Demo for this use case: To run this code, open the terminal at the bottom and run "npx ts-node ./use-cases/enforce-one-class-per-file/"

Let's break it down, there are a few key terms that you need to know:

- Program

- Source File

- Node

- Declaration

TypeScript Program

When working with the TypeScript Compiler, one of the central elements you'll encounter is the Program object. This object serves as the starting point for many of the operations you might want to perform, like type checking, emitting output files, or transforming the source code.

The Program is created using the ts.createProgram function, which can accept a variety of configuration options, such as

options: These are the compiler options that guide how the TypeScript Compiler will behave. This could include settings like the target ECMAScript version, module resolution strategy, and whether to include type-checking errors, among others.rootNames: This property specifies the entry files for the program. It is an array of filenames (.ts) that act as the roots from which the TypeScript Compiler will begin its operations.projectReferences: If your TypeScript project consists of multiple sub-projects that reference each other, this property is used to manage those relationships.configFileParsingDiagnostics: This property is an array that will capture any diagnostic information or errors that arise when parsing the tsconfig.json file. More on that later.

const tsconfigPath = './tsconfig.json'; // path to your tsconfig.json

const tsConfigParseResult = parseTsConfig(tsconfigPath);

const program = ts.createProgram({

options: tsConfigParseResult.options,

rootNames: tsConfigParseResult.fileNames,

projectReferences: tsConfigParseResult.projectReferences,

configFileParsingDiagnostics: tsConfigParseResult.errors,

});In this sample, a TypeScript program is created from tsconfig parsing results.

Source File

Writing code is actually writing text, you understand it because you know the language, the semantics, the syntax, etc. But the computer doesn't understand it, it's just a text.

The compiler will take this text and transform it into something that can be utilised. This transformation is called parsing and its output is called Abstract Syntax Tree (AST).

A source file is a representation of a file in your project, it contains information about the file, such as its name, path, and contents.

The AST is a tree-like data structure and as any tree, it has a root node. The root node is Source File.

Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)

The code you write is essentially a text that isn't useful unless it can be parsed. That parsing process produces a tree data structure called AST, it contains a lot of information like the name, kind, and position of the node in the source code.

The AST is used by the compiler to understand the code and perform various operations on it. For example, the compiler uses the AST to perform type-checking.

The following code:

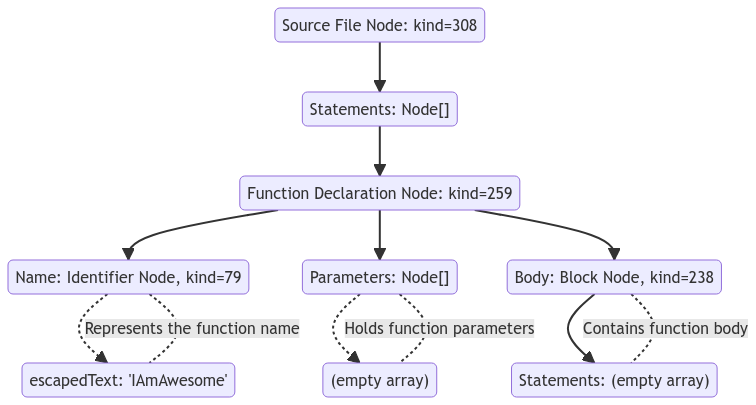

function IAmAwesome() {}will be transformed into the following AST:

{ // -> Source File Node

"kind": 308,

"statements": [ // -> Node[]

{ // -> Function Declaration Node

"kind": 259,

"name": { // -> Identifier Node

"kind": 79,

"escapedText": "IAmAwesome"

},

"parameters": [], // Node[]

"body": { // Block Node

"kind": 238,

"statements": []

}

}

]

Node

In AST, the fundamental unit is called a Node.

Kind: A numeric value that represents the specific type or category of that node. For instance:

- FunctionDeclaration has kind 259

- Block has kind 238

These numbers are exported in an enum called SyntaxKind

The node object has more than just these properties but right now we're only interested in a few, nonetheless, two additional important properties you might want to know about are:

Parent: This property points to the node that is the parent of the current node in the AST.

Flags: These are binary attributes stored as flags in the node. They can tell you various properties of the node, such as whether it's a read-only field or it has certain modifiers.

Declaration

Remember the use case you're trying to solve? enforce one class per file. To do that, you need to check if more than one class is declared in the file.

A declaration is a node that declares something, it could be a variable, function, class, etc.

class Test {

runner: string = 'jest';

}In this example, we have two declarations:

Test->ClassDeclarationrunner->PropertyDeclaration

The key difference between a node and a declaration is that

-

A "Node" is a generic term that refers to any point in the AST, irrespective of what it represents in the source code.

-

A "Declaration" is a specific type of node that has a semantic role in the program: it introduces a new identifier and provides information about it.

Creating a variable

const a = 1;is like saying "Hey compiler, I'm creatingVariableDeclarationnode with nameaand value1"

Statement

A statement is a node that represents a statement in the source code. A statement is a piece of code that performs some action, for example, a variable declaration is a statement that declares a variable.

let a = 1;In this example the variable declaration let a = 1; is a statement.

Expression

An expression is a node in the code that evaluates to a value. For example

let a = 1 + 2;The part 1 + 2 is an expression, specifically a binary expression

Another example

const add = function addFn(a: number, b: number) {};The function ... is an expression, specifically a function expression.

More advanced example

const first = 1,

second = 2 + 3,

third = whatIsThird();- The whole code is a

VariableStatementnode. first = 1,second = 2 + 3andthird = whatIsThird()are aVariableDeclarationnodes.first,second, andthirdareIdentifiernodes.1,2 + 3, andwhatIsThird()areNumericLiteral,BinaryExpression, andCallExpressionnodes respectively.

Use Case: No Function Expression

Let's take another example to recap what you've learned so far. You're going to use the Typescript Compiler API to enforce no function expression.

- Function Declaration:

function addFn(a: number, b: number) {

return a + b;

}- Function Expression

let addFnExpression = function addFn(a: number, b: number) {

return a + b;

};You need to ensure only the first one is allowed.

type Transformer = (

file: ts.SourceFile

) => ts.TransformerFactory<ts.SourceFile>;

const transformer: Transformer = file => {

return function (context) {

const visit: ts.Visitor = node => {

if (ts.isVariableDeclaration(node)) {

if (node.initializer && ts.isFunctionExpression(node.initializer)) {

throw new Error(`

No function expression allowed.

Found function expression: ${node.name.getText(file)}

File: ${file.fileName}

`);

}

}

// visit each child in this node (look at the visitor node parameter)

return ts.visitEachChild(node, visit, context);

};

// visit each node in the file

return node => ts.visitEachChild(node, visit, context);

};

};

const files = program.getSourceFiles();

files

.filter(file => !file.isDeclarationFile)

.forEach(file =>

ts.transform(file, [transformer(file)], program.getCompilerOptions())

);I know this isn't like the first example, but it's similar.

In the first use case, it was enough to loop over the first level nodes in the file, but in this use case, you need to loop over all nodes in the file, the nested ones as well.

The main logic is within the visit function, it checks if the node is a VariableDeclaration and whether its initializer is a FunctionExpression, and if so, then throws an error.

The looping over the files is the same but with a slight difference, you're using ts.transform API.

A few key terms that you need to know:

- Transformer

- Visitor

- Context

Demo for this use case: To run this code, open the terminal at the bottom and run "npx ts-node ./use-cases/no-function-expression"

Transformer

As the name implies, the transformer function can transform the AST (the code) in any way you want. In this example, you're using it to enforce a rule, however, instead of throwing an error, you can transform the code to fix the error (more in the next use case)

Visitor

The visit function is a simpler version of what is called the Visitor Pattern, an essential part of how the TypeScript Compiler API works. Actually, you'll see that design pattern whenever you work with AST, Hey at least I did!

A "visitor" is basically a function you define to be invoked for each node in the AST during the traversal. The function is called with the current node and has few return choices.

- Return the node as is (no changes).

- Return a new node of the same kind (otherwise might disrupt the AST) to replace it.

- Return undefined to remove the node entirely.

- Return a visitor

ts.visitEachChild(node, visit, context)which will visit the node children if have.

Context

The context -TransformationContext- is an object that contains information about the current transformation and has a few methods that you can use to perform various operations like hoistFunctionDeclaration and startLexicalEnvironment. You'll learn more about it in the next use case.

Use Case: Replace Function Expression With Function Declaration

Same as the previous use case, but instead of throwing an error, you're going to transform function expression to function declaration.

See how the AST for the function expression looks like

const transformer: Transformer = function (file) {

return function (context) {

const visit: ts.Visitor = node => {

if (ts.isVariableStatement(node)) {

const varList: ts.VariableDeclaration[] = [];

const functionList: ts.FunctionExpression[] = [];

// collect function expression and variable declaration

for (const declaration of node.declarationList.declarations) {

// the initializer is expression after assignment operator

if (declaration.initializer) {

if (ts.isFunctionExpression(declaration.initializer)) {

functionList.push(declaration.initializer);

} else {

varList.push(declaration);

}

}

}

for (const functionExpression of functionList) {

// create function declaration out of function expression

const functionDeclaration = ts.factory.createFunctionDeclaration(

functionExpression.modifiers,

functionExpression.asteriskToken,

functionExpression.name as ts.Identifier,

functionExpression.typeParameters,

functionExpression.parameters,

functionExpression.type,

functionExpression.body

);

// hoist the function declaration to the top of the containing scope (file)

context.hoistFunctionDeclaration(functionDeclaration);

}

// if the varList (non function expression) is same as the original variable statement, return the node as is.

// it means there is no function expression in the variable statement

if (varList.length === node.declarationList.declarations.length) {

return node;

}

// if the varList (non function expression) is empty, return undefined to remove the variable statement node

if (varList.length === 0) {

return undefined;

}

return ts.factory.updateVariableStatement(

node,

node.modifiers,

ts.factory.createVariableDeclarationList(varList)

);

}

return ts.visitEachChild(node, visit, context);

};

return node => {

// Start a new lexical environment when beginning to process the source file.

context.startLexicalEnvironment();

// visit each node in the file.

const updatedNode = ts.visitEachChild(node, visit, context);

// End the lexical environment and collect any declarations (function declarations, variable declarations, etc) that were added.

const declarations = context.endLexicalEnvironment() ?? [];

const statements = [...declarations, ...updatedNode.statements];

return ts.factory.updateSourceFile(

node,

statements,

node.isDeclarationFile,

node.referencedFiles,

node.typeReferenceDirectives,

node.hasNoDefaultLib,

node.libReferenceDirectives

);

};

};

};A few key terms that you need to know:

- Factory

- Lexical Environment

- Hoisting

Demo for this use case: To run this code, open the terminal at the bottom and run "npx ts-node ./use-cases/replace-function-expression-with-declaration"

Factory

The ts.factory object contains a set of factory functions that can be used to create new nodes or update existing ones. You used ts.factory.createFunctionDeclaration to create a new function declaration node using the information from the function expression node and ts.factory.updateSourceFile to update the source file node statements while keeping the other properties intact.

The factory functions are useful to manipulate the AST in a safe way, without worrying about the details of the AST structure.

Lexical Environment

The lexical environment refers to the scope or context in which variables and function declarations are hoisted and managed during the transformation process.

Here are the key points regarding the lexical environment in your transformer function:

-

Scope Management: The lexical environment helps in managing the scope of variables and function declarations. When you start a new lexical environment with

context.startLexicalEnvironment(), you are essentially marking the beginning of a new scope. When you end it withcontext.endLexicalEnvironment(), you are closing off that scope and collecting any declarations that were hoisted to this scope during the transformation process. -

Hoisting: The lexical environment provides the facilities for hoisting function declarations using

context.hoistFunctionDeclaration(). Hoisting in this scenario means moving function declarations to the appropriate scope in the source file (the current running scope). For instance, if you have a function declaration inside a function, it will be hoisted to the top of the function, if you have a function declaration inside a for loop, it will be hoisted to the top of the for loop, and so on.The previous code only handles the function expression at the top level

-

Declaration Collection: The lexical environment also collects the hoisted declarations through

context.endLexicalEnvironment(). This method returns an array of Statement nodes that represent the declarations hoisted to the current lexical environment, which can then be included in theSourceFilenode.

These methods ensure that the transformer has a mechanism to correctly manage scope and collect hoisted declarations, which is crucial for accurately transforming code while maintaining correct scoping and semantics.

Use Case: Detect Third-Party Classes Used as Superclasses

The last use case is a bit more complex, you're going to use the Typescript Compiler API to detect third-party classes used as superclasses, not to do anything about it, just detect them which means you don't need to use the transformer function.

const trackThirdPartyClassesUsedAsSuperClass: ts.Visitor = node => {

if (ts.isClassDeclaration(node)) {

const superClass = (node.heritageClauses ?? []).find(

heritageClause => heritageClause.token === ts.SyntaxKind.ExtendsKeyword

);

// Not intrested in classes that don't have super class.

if (!superClass) {

return node;

}

// in case of class declaration, there will always be one heritage clause (extends)

const superClassType = superClass.types[0].expression;

// Get the type checker

const typeChecker = program.getTypeChecker();

const symbol = typeChecker.getSymbolAtLocation(superClassType);

if (!symbol) {

return undefined;

}

const superClassDeclaration = (symbol.declarations ?? []).find(

ts.isClassDeclaration

);

if (!superClassDeclaration) {

// In this case this should never happen (more on that later),

// but it's here just to satisfy typescript.

return node;

}

const thisSourceCodeFile = node.getSourceFile();

const sourceCodeInfo = {

fileName: thisSourceCodeFile.fileName,

className: node.name?.text,

...ts.getLineAndCharacterOfPosition(thisSourceCodeFile, node.pos),

};

const thirdPartyCodeInfo = {

fileName: superClassDeclaration.getSourceFile().fileName,

className: superClassType.getText(),

};

console.log(`

Class: "${sourceCodeInfo.className}"

Filename: "${sourceCodeInfo.fileName}"

SuperClass: "${thirdPartyCodeInfo.className}"

Filename: "${thirdPartyCodeInfo.fileName}"

Line: "${sourceCodeInfo.line}"

Column: "${sourceCodeInfo.character}"

`);

}

// visit each child in this node

return ts.forEachChild(node, trackThirdPartyClassesUsedAsSuperClass);

};

const files = program.getSourceFiles();

files

.filter(file => !file.isDeclarationFile)

.forEach(file => {

ts.forEachChild(file, trackThirdPartyClassesUsedAsSuperClass);

});Key terms that you need to know:

- HeritageClauses

- Type

- Type Checker

- Symbol

Demo for this use case: To run this code, open the terminal at the bottom and run "npx ts-node ./use-cases/3rd-party-classes/"

HeritageClauses

When you extend a class or implement an interface, you use a clause called a heritage clause and it's represented by the HeritageClause interface.

interface HeritageClause {

readonly token: SyntaxKind.ExtendsKeyword | SyntaxKind.ImplementsKeyword;

readonly types: NodeArray<ExpressionWithTypeArguments>;

}_ token is the keyword used in the clause, it can be extends or implements._

_ types is an array of ExpressionWithTypeArguments nodes, which represents the types specified in the clause._

types will have a single item if you're extending a class or multiple items if you're implementing interfaces.

In this example, you're only interested in the extends hence const [superClass] = node.heritageClauses

Type

It is the "Type" part in TypeScript 😏, representing the type information of a particular symbol in the AST.

A Type object is associated with a Symbol to represent the type of the symbol (named entity).

interface Type {

flags: TypeFlags;

symbol: Symbol;

}-

flags: The flags associated with the type which can be used to determine the kind of type -number, string, boolean, etc.- -

symbol: The symbol associated with the type (scroll a bit to read about symbols)

Type Checker

It is an essential part of the TypeScript Compiler API, acting as the engine that powers the type system in TypeScript. The Type Checker traverses the AST, examining the Type and Symbol of nodes to ensure they adhere to the type annotations and constraints defined in the code.

The Type Checker can be accessed via the program object, and it provides a rich set of methods to retrieve type information, check types, and obtain symbol information, among other functionalities.

const typeChecker = program.getTypeChecker();In this use case, you used typeChecker to get the type of the class declaration node and the symbol associated with it, which you then used to get the value declaration of the symbol.

const type = typeChecker.getTypeAtLocation(node);

const symbol = type.symbol;

const valueDeclaration = symbol.valueDeclaration;TypeChecker has a lot of methods to facilitate working with types, symbols, and nodes.

Symbol

The term "symbol" refers to a named entity in the source code that could represent variables, functions, classes, and so forth.

named entity is a name that is used to identify something. It could be a variable name, function name, class name, etc. In other words any Identifier Node.

A symbol is represented by the Symbol interface, which has the following properties:

interface Symbol {

flags: SymbolFlags;

escapedName: __String;

declarations?: Declaration[];

valueDeclaration?: Declaration;

members?: SymbolTable;

exports?: SymbolTable;

globalExports?: SymbolTable;

}flags: The flags associated with the symbol which can be used to determine the type of symbol -variable, function, class, interface, etc.-escapedName: The name of declarations associated with the symbol.declarations: List of declarations associated with the symbol, think of function/method override.valueDeclaration: Points to the declaration that serves as the "primary" or "canonical" declaration of the symbol. In simpler terms, it's the declaration that gives the symbol its "value" or "meaning" within the code. For example, if you have a variable initialized with a function, the valueDeclaration would point to that function expression.members: Symbol table that contains information about the properties or members of the symbol. For instance, if the symbol represents a class, members would contain symbols for each of the class's methods and properties.exports: Similar to members, but this is more relevant for modules. It contains the symbols that are exported from the module.globalExports: This is another symbol table but it's used for global scope exports.

Let's take the following example

class Test {

runner: string = 'jest';

}The symbol for class "Test" will have the following properties:

const classTestSymbol = {

flags: 32,

escapedName: "Test",

declarations: [ClassDeclaration],

valueDeclaration: ClassDeclaration,

members: {

runner: // Symbol for runner property

},

};Symbols let the type checker look up names and then check their declarations to determine types. It also contains a small summary of what kind of declaration it is -- mainly whether it is a value, a type, or a namespace.

Diagnostic

When the TypeScript compiler runs, it performs several checks on the code. If it encounters something that doesn't align with the language rules or the project's configuration, it creates an object that represents identified issues the compiler has found in the code.

Each diagnostic object contains information about the nature of the problem, including:

- The file in which the issue was found.

- The start and end position of the relevant code.

- A message describing the issue.

- A diagnostic category (error, warning, suggestion, or message).

- A code that uniquely identifies the type of diagnostic.

The issues can range from syntax errors and type mismatches to more subtle semantic issues that might not be immediately apparent. Mainly, there are two kinds of diagnostics:

-

Syntactic Diagnostics: These are errors that occur when the compiler parses the code and encounters something that doesn't align with the language syntax. For instance, if you have a missing semicolon or a missing closing brace, the compiler will generate a syntactic diagnostic.

-

Semantic Diagnostics: These are errors that occur when the compiler performs type-checking on the code and encounters something that doesn't align with the type annotations or constraints defined in the code. For instance, if you have a variable of type string and you try to assign a number to it, the compiler will generate a semantic diagnostic.

Here's a simple example of how you might encounter a diagnostic in TypeScript:

let greeting: string = 42;The TypeScript compiler will generate a diagnostic message for the above code, indicating that the type 'number' is not assignable to the type 'string'.

To obtain semantic diagnostics, you can use the getSemanticDiagnostics method on the program object. This method returns an array of diagnostic objects, each of which contains information about the issue, such as the file in which it was found, the start and end position of the relevant code, and a message describing the issue.

program.getSemanticDiagnostics();Will return

[

{

"start": 0,

"length": 8,

"code": 2322,

"category": 1,

"messageText": "Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'string'.",

"relatedInformation": undefined

}

]To obtain syntactic diagnostics

// missing expression after assignment operator

let greeting: string =;

// get syntactic diagnostics

program.getSyntacticDiagnostics();Will return

[

{

"start": 0,

"length": 1,

"messageText": "Expression expected.",

"category": 1,

"code": 1109,

"reportsUnnecessary": undefined

}

]Diagnostics are not just for the compiler; they are also used by IDEs and editors to provide real-time feedback to developers. For example, when you see red squiggly lines under code in Visual Studio Code, that's the editor using TypeScript diagnostics to indicate an issue.

Here's a snippet that demonstrates how to retrieve diagnostics for a given TypeScript program before emitting the output files:

// Retrieve and concatenate all diagnostics

const allDiagnostics = ts.getPreEmitDiagnostics(program);

// Iterate over diagnostics and log them

allDiagnostics.forEach(diagnostic => {

if (diagnostic.file) {

let { line, character } = diagnostic.file.getLineAndCharacterOfPosition(

diagnostic.start!

);

let message = ts.flattenDiagnosticMessageText(diagnostic.messageText, '\n');

console.log(

`${diagnostic.file.fileName} (${line + 1},${character + 1}): ${message}`

);

} else {

console.log(ts.flattenDiagnosticMessageText(diagnostic.messageText, '\n'));

}

});You might have noticed the function says pre-emit getPreEmitDiagnostics which implies there will be diagnostics after the emit process, and you're right, there are.

The post-emit diagnostics are generated after the emit process, and they are used to report issues that might arise during the emit process. For instance, there might be issues with generating source maps or writing output files.

Printer

TypeScript provides a printer API that can be used to generate source code from an AST, it is useful when you want to perform transformations on the AST and then generate the corresponding source code in text format.

function print(file: ts.Node, result: ts.TransformationResult<ts.SourceFile>) {

const printer = ts.createPrinter({

newLine: ts.NewLineKind.LineFeed,

});

const transformedSource = printer.printNode(

ts.EmitHint.Unspecified,

result.transformed[0],

file

);

return transformedSource;

}In use case 3, you'll need to write the modified AST to the original file back, to do that you'll need to use the printer API to get the AST into text.

Worth mentioning that the printer doesn't preserve the original formatting of the source code.

For this exact reason I don't recommend direct use of the compiler API to modify source code, instead, I use ts-morph which is a wrapper around the compiler API that preserves the original formatting.

How The Compiler Works

The following is a high-level overview.

Lexical Analysis

In this stage, the compiler takes the source code and breaks it down into a series of tokens, a token is a character or sequence of characters that can be treated as a single unit.

function IAmAwesome() {}Will be transformed into the following tokens:

<function, keyword>

<IAmAwesome, identifier>

<(, punctuation>

<), punctuation>

<{, punctuation>

<}, punctuation>The module/function that does this is called the Scanner/Tokenizer which is responsible for scanning the source code and generating the tokens. When the term scanner/tokenizer is used, imagine a while loop that loops over the source code character by character and switch case to determine the token type.

function scan(sourceCode: string) {

const tokens: Token[] = [];

let currentChar: string;

let index = -1;

do {

index = index + 1;

currentChar = sourceCode[index];

} while (index < sourceCode.length);

{

switch (currentChar) {

case '{':

// ...

break;

case '}':

// ...

break;

// ...

}

}

}Syntax Analysis

In this stage, the compiler takes the tokens generated in the previous stage and uses them to build a tree-like structure called an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). The AST represents the syntactic structure of the source code.

The part of the compiler that does this is called the Parser which is responsible for parsing the tokens and building the AST that is then used by the semantic analysis stage.

So the Tokensizer generates the tokens and the Parser builds the AST. You may be wondering (are you?) how the parser knows what the AST should look like, well, it's defined in the Language Grammar.

A grammar is a set of rules that define the syntax of a language. Think of English grammar, it defines the rules of the English language, such as how to form a sentence, how to use punctuation, etc.

Grammar is usually represented in a form called Backus-Naur Form (BNF) or Antlr, which is a notation that describes the grammar of a language.

A simple example of grammars:

<identifier> ::= "a" | "b" | "c" | ... | "z"

<function> ::= "function" <identifier>* "(" ")" "{" "}"The parser will use the grammar to build the AST, in case of writing a function, the parser will look for the function keyword, then the identifier, the (, the ), the {, then the } in case of any of these tokens is missing, the parser will throw an error. Read More on parsing

<postal-address> ::= <name-part> <street-address> <zip-part>

<name-part> ::= <personal-part> <last-name> <opt-suffix-part> <EOL> | <personal-part> <name-part>

<personal-part> ::= <first-name> | <initial> "."

<street-address> ::= <house-num> <street-name> <opt-apt-num> <EOL>

<zip-part> ::= <town-name> "," <state-code> <ZIP-code> <EOL>

<opt-suffix-part> ::= "Sr." | "Jr." | <roman-numeral> | ""

<opt-apt-num> ::= "Apt" <apt-num> | ""Semantic Analysis

At this stage, the TypeScript compiler performs semantic analysis on the AST generated during the parsing stage to ensure that the syntactically correct code is also semantically valid. For instance, consider the following TypeScript snippet:

let a = 1;

a();While the parser confirms this code is free of syntax errors, semantic analysis reveals a type error. This code tries to invoke a as if it were a function, which is semantically incorrect since a is a number.

The semantic analysis phase comprises two key processes: Binding and Type Checking.

Binding: It walks the AST and creates symbols for all declarations it encounters, such as variables, functions, classes, etc.

- A Symbol is created for each declaration, capturing its name, type, scope, and additional attributes.

- The symbol is then stored in a SymbolTable, which is essentially a map that associates symbols with their names and is scoped to a specific block, function, or module.

The internal representation of a SymbolTable in TypeScript might look something like this:

type SymbolTable = Map<__String, Symbol>;The function to create such a table could be as follows:

export function createSymbolTable(symbols?: readonly Symbol[]): SymbolTable {

const result = new Map<__String, Symbol>();

if (symbols) {

for (const symbol of symbols) {

result.set(symbol.escapedName, symbol);

}

}

return result;

}Read more on the binding process

Type Checking: The Type Checker takes over after binding. It uses the symbol table to verify that each symbol's usage is consistent with its declared type. In the provided code example, the type checker identifies that a is a number and cannot be invoked, raising a compile-time error.

While Binding and Type checking are distinct processes, they are interdependent. The Binder populates the symbol table necessary for the Type Checker to verify the correct usage of types. Conversely, the Type Checker may influence the binding process, particularly in complex scenarios involving type inference or generics.

Emitting

This is where the compiler generates the output files, such as JavaScript files, source maps, and declaration files after the AST has been successfully created and type-checked.

project.emit();Recall diagnostics? the emit process will fail if there are any errors but that can be overridden by setting noEmitOnError to true.

ESLint

Using ESLint is a better option if you want to enforce rules on your codebase because it's specifically built for that purpose. However, if you want to build a tool that does something more complex, then the Typescript Compiler API is the way to go.

I have written a guide for you to learn more.

Conclusion

The TypeScript Compiler API is a powerful tool that can be used to build tools around TypeScript. It provides a rich set of functionalities that can be used to perform various operations on the source code, such as type checking, code generation, and AST transformation.

It's a bit confusing at first, but once you get the hang of it, you'll be able to build some cool stuff.

You can also generate TypeScript code using the API, think of protobuf to TypeScript code generator.

Next Steps

Practice, practice, practice. The best way to learn is to practice what you've learned here. Try to build a tool that does something useful for you or your team.

Think of manual tasks -typescript-related- that you do often and try to automate them. Stuff that is error-prone, time-consuming, or just boring.

I'm writing a few other blog posts that will help you get started with the Typescript Compiler API, follow me on Twitter to get notified when they're out.

References

- Codebase Compiler Binder

- TypeScript Compiler Notes

- TypeScript Transformer Handbook

- TypeScript Source Code

- What Is Semantic Analysis in a Compiler?

Related Projects

Credits

- The graph tree was generated using Mermaid JS

- The drawing was created using Excalidraw

- Image caption were generated using ChatGPT